Savonia Article: Pandemic pressures: How COVID-19 re-shaped Finland’s healthcare system

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 pandemic constituted a serious strain on health care systems across the world including the publicly funded and decentralized model in Finland. Even though the rate of infection and mortality was relatively low compared to many other European countries, the crisis had its own chain of underpinning consequences. The fast redistribution of electronic resources to reduce the spread of viruses created imbalances of care not requiring immediate attention, therefore creating massive backlogs of delayed services and other healthcare-related problems for patients and healthcare staff.

DEFERRED AND BACKLOG-RELATED CONSEQUENCES

Reduction of Non-Urgent Care and Growing Waitlist

When COVID-19 initially found its way to the Finnish territory at the start of 2020, healthcare planners focused on the mode of increasing emergency and intensive-care capacity, which required a reallocation of staff and hospital resources in a bid to cope with the rising COVID-patients. As a result, services that were not of urgent nature were postponed across the country, including elective procedures, out-patient consultations, and screenings (THL, 2022). Although the approach was successful in protecting the intensive-care workforce by limiting patient numbers and preserving ICU capacity, it also created a backlog in the service pipeline which was cleared over a period of two years.

An especially instructive influence concerns elective urological procedures. For example, in two consecutive doctor-reports, Uimonen et al. (2021) reported that elective urology surgeries saw a significant decrease at three Finnish hospital sites during the lockdown period of 2020, and it did not all recover during the following year (Uimonen et al., 2021, 34-36). These delays caused logistical problems as well as clinical consequences such as prolonged discomfort in patients and post-ponement of the diagnosis.

Side by side with this, the dental industries were also impacted by the pandemic. According to THL, almost 1.3 million people missed their dentist appointment in the peak pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, many of which they had not yet booked or postponed to 2022. Such care gaps increased the potential of more severe oral-health issues, which could become the cost and morbidity driver in the future.

Regional Variations and Mental Health Service Delays

Different geographic areas were affected differently regarding the severity of the pandemic. Those municipalities with a high number of cases, in particular Helsinki and Uusimaa, had the most severe delays. According to November 2021 reports by Yle News, the number of patients waiting to receive callbacks at healthcare centers in the queue area of the capital region exceeded 6000 people, leading to the growth of the night and weekend schedule of operations to handle the built-up demand (Yle). The decentralized nature of the Finnish healthcare structure where medical services are provided at the municipal level made access to limited-resource centers less capable of holding continuity, deepening regional inequality of access even further.

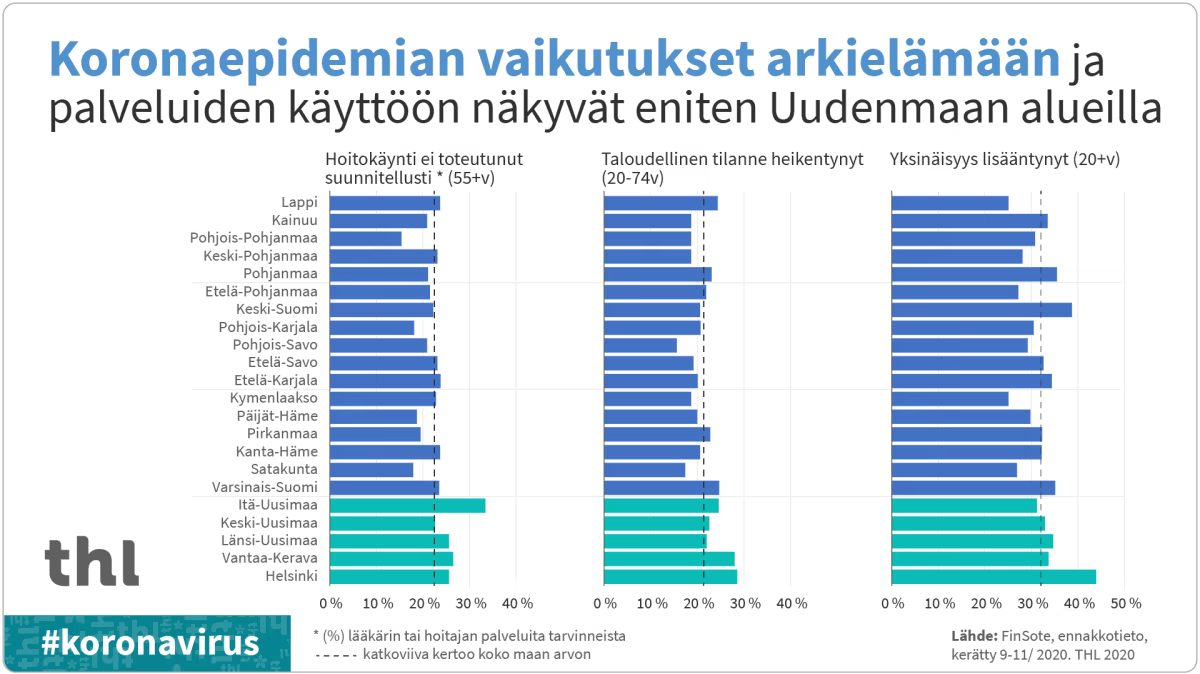

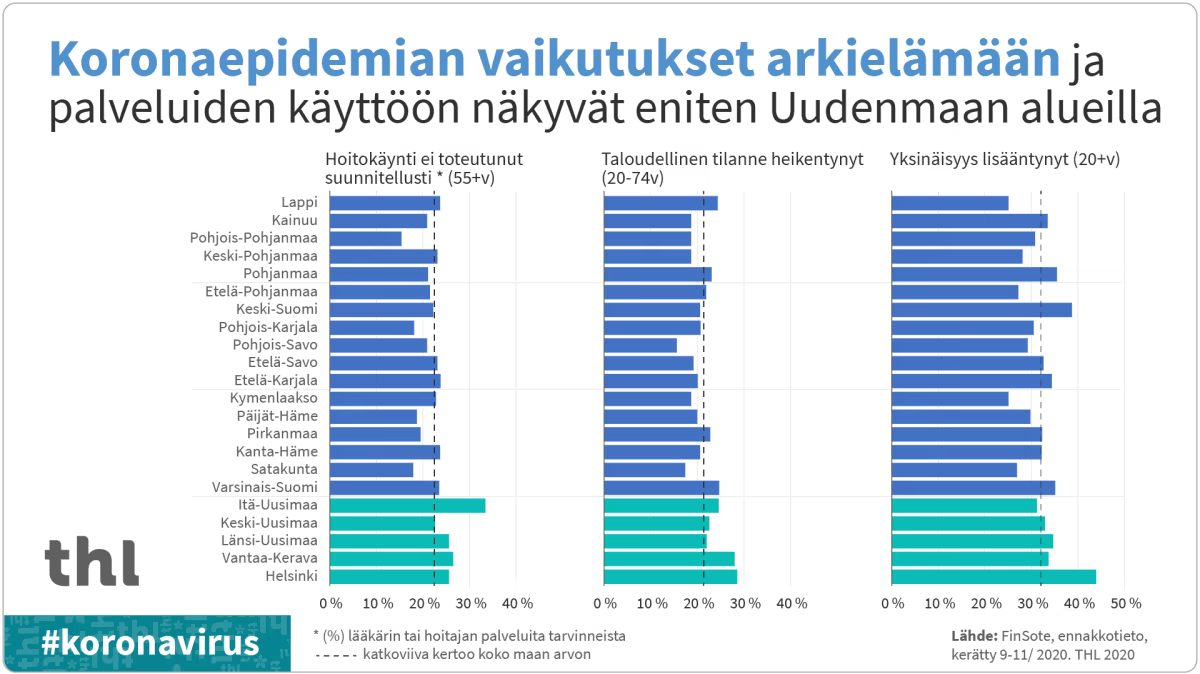

The results of the FinSote survey in Figure 1 shows that the effects of the COVID-19 epidemic and related restrictions on the population’s well-being and access to services vary clearly across different parts of Finland. The chart highlights the impact of the pandemic on healthcare appointments, economic conditions, and social isolation in various regions, with particular emphasis on the Uusimaa region. The data shows that healthcare visits were most affected in the Uusimaa area, and economic conditions worsened, especially in regions like Uusimaa and Kanta-Häme. (THL), 2020.

Distinct differences can be seen between wellbeing services counties in how medical appointments have been cancelled or delayed, how the epidemic has weakened people’s economic and social situations, and how it has affected lifestyles.

The impacts on doctor visits and everyday life are most pronounced in the Uusimaa region, where the COVID-19 epidemic has been the most severe.

Increased mental-health-service pressure became particularly worrisome. There was a steep increase in the demand for psychiatric assessment and counselling particularly by the adolescents and young adults but the lack of workforce especially psychologists and psychiatrists hindered proficient response. The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL, 2022) noted that waiting time in specialized mental-health care lengthened significantly between 2019 and 2021 even after the number of persons in the population with an indicator of anxiety or depression rose (THL, 2022).

LONG-TERM HEALTH EFFECTS AND WORKFORCE STRAIN

Persistent Symptoms and Rehabilitation Needs

A large percentage of Finnish patients recovering from COVID-19 show long lasting effects, espe-cially those who have already been admitted to hospital. As indicated by Lindahl et al. (2022), 79 % of the patients under consideration continued to use healthcare services one year after the discharge, and nearly 10 % did not go back to work (Lindahl et al., 2023, p. 377)). Common sequelae, that is, fatigue, breathlessness, and reduced lung function often required a rehabilitation intervention (Lindahl et al. 376-378). These aftereffects that are commonly termed as long-COVID, cause new problems to the healthcare system. The presence of the traditionally solid acute-care infrastructure in Finland has been forced to transform with the development of the multidisciplinary models of care. To care efficiently about the long COVID, as the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL, 2022) notes, integration of physical and mental health care services needs to be stronger, even if these are the areas where capacity remains limited.

Burnout Among Healthcare Workers

At the same time, there was a major psychological pressure exerted on Finnish healthcare staff. Among hospital personnel, anxiety, sleeplessness, and burnout are heterogeneous yet measurable during the first year of the pandemic because certain related metrics increase gradually over time (Rosenström et al. 2022). Six months later into the crisis, nurses and other members of staff at Helsinki University Hospital showed a high level of psychological distress (Laukkala et al. 2021). Such psychological pressures reflect and exacerbate labor deficits that are occurring at times of pandemic peaks.

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 pandemic has introduced long-term and far-reaching consequences to Finland health care system, on the one hand, displaying the strengths and vulnerabilities thereof. The phenomenon of substantial backlog in non-urgent services, such as elective surgeries and dental care, is still caus-ing massive burdens to the service provision and outcomes (THL, 2022; Uimonen et al., 2021).

The effect of increased demand of mental health services and long-term staff shortages is exacer-bated by the elevated levels of pressure, especially in areas where the outbreak remained high (Yle, 2021; Rosenström et al., 2022).

Moreover, chronic health issues faced by survivors of COVID-19, including the presence of long-term symptoms and rehabilitation demands, add yet another burden to resources and justify com-prehensive cross-disciplinary care (Lindahl et al., 2023; THL, 2022).At the same time, the health of healthcare staff is an emerging problem due to the high level of burnout and mental distress (Rosenström et al., 2022).

Such multi-issue problems require continuous investment in medical staff, electronic infrastructure, and mental conditions support.

Authors:

Hiltunen, Sanni, IN23SP, Savonia UAS, s2305266@edu.savonia.fi

Mensah-Attipoe, Jacob, Part-time lecturer, Savonia UAS, Jacob.mensah-attipoe@savonia.fi

References:

Laukkala, T., et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Helsinki University Hospital Personnel Psychological Well-Being: Six-Month Follow-Up Results. International Journal of Environmental Research and Pub-lic Health. 2021;18(5):2524. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/5/2524. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Lindahl, A., et al. Persisting Symptoms Common but Inability to Work Rare: A One-Year Follow-Up Study of Finnish Hospitalised COVID-19 Patients. Infectious Diseases (London). 2023;55(6):375–383. Taylor & Francis Online. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37560984. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Rosenström, T., et al. Healthcare Workers’ Heterogeneous Mental-Health Responses to Prolonging COVID-19 Pandemic: A Full Year of Monthly Follow-Up in Finland. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:724. Springer Nature. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-022-04389-x. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Uimonen, M., et al. Healthcare Lockdown Resulted in a Treatment Backlog in Elective Urological Sur-gery during COVID-19. BJU International. 2021;128(1):33–41. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8251249. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic and Staff Shortage Increased Backlog in Care and Treatment – THL Assesses Finland’s Health and Social Services. 6 Apr. 2022. https://thl.fi/en/-/prolonged-covid-19-pandemic-and-staff-shortage-increased-backlog-in-care-and-treatment-thl-assesses-finland-s-health-and-social-services. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Yle. THL: COVID-19 Backlog in Finland Includes 1.3 Million Missed Dental Visits. Yle Uutiset. 28 Nov. 2021. https://yle.fi/a/3-11601590. Accessed 3.11.2025.

Yle. Näin korona iski suomalaisten hyvinvointiin: erityisesti pääkaupunkiseutu kovilla, kertoo THL:n kysely – katso oman maakuntasi tulokset. 16 Dec. 2020. https://yle.fi/a/3-11697651. Accessed 3.11.2025.

OpenAI. ChatGPT. 17 July 2025. chat.openai.com. Accessed 17 July 2025. (Used to find reliable resources)