Savonia Article: Emotional exhaustion among finnish nurses in acute care settings and targeted interventions

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Abstract

Burnout among nurses has been a global concern. The fundamental aspect of burnout is emotional exhaustion, which is frighteningly widespread among acute-care Finnish nurses. This article examines the contemporary prevalence and predictors of emotional exhaustion within Finnish hospitals and emergency departments, expounds on the available evidence of the outcomes, and, most crucially, recommends specific, practical, and evidence-based interventions that have already demonstrated their potential in Finland or other similar Nordic healthcare settings. The intention is to provide the nurse managers, occupational health professionals, and individual nurses with practical tools to prevent and avoid emotional exhaustion before they become sickness absences, turnover, or undermined patient safety.

Keywords: emotional exhaustion, burnout, acute care nursing, Finnish nurses, intervention, wellbeing at work

1 INTRODUCTION

Emotional management is not a soft skill, but an essential underpinning of mental health, good social performance and goal-oriented behavior that is essential in a work environment, particularly in the medical field (Gross, 2015). As the source of emotional support to patients and family, nurses engage in emotional labor, i.e., the process of affecting and controlling their emotions to conform to the requirements of their work (Hossain et al., 2024). This emotional effort is draining and very high.

Various reports have also indicated that globally and especially in the strenuous high stake’s workplace (i.e., emergency departments and intensive care units), nurses are reported to be suffering alarming amounts of emotional exhaustion which is one of the main dimensions of job burnout (Maslach et al., 2001). This is not a case of an instant sensation or a personal deficiency, but an institutional problem and needs solutions that are at the societal level and must be overhauled (Ruotsalainen et al., 2022). Within the Finnish scenario such problem is augmented by the chronic, long-standing staffing deficits and the strain of preserving the quality of care that is anticipated of the Nordic welfare model (Koivula et al., 2000).

The process of emotional exhaustion is not achieved within a short period of time. It is caused by known factors, such as too much work, acuity of patients, the absence of professional autonomy, and regular exposure to the trauma and death defining acute care (Aylward et al., 2021). These outcomes of this depletion are quite clear and extensive as they are not only the pain of the individual nurse but also the negative effects on patient safety and the quality of care provided on a global scale to the whole healthcare system (Samarakoon & Wickramasinghe, 2025). The capacity to give caring, keen and faultless care is essentially tampered when a nurse is operating on empty. This article aims to explore the emotional exhaustion among Finnish nurses in acute care settings and propose a framework of targeted interventions.

1.1 Purpose of the article

This article is aimed at achieving three things:

Specifically, this article aims to describe the prevalence and risk factors of emotional exhaustion among Finnish acute care nurses, critically summarize the implications for nurses, patients, and the healthcare system, and suggest a multi-level interventions and evidence-based remedies to address emotional exhaustion in this demographic.

2 PREVALENCE OF EMOTIONAL EXHAUSTION AMONG FINNISH NURSES

Emotional exhaustion refers to the experience of being psychologically overstretched and tired of all of the available emotional and physical resources (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). It is the oldest and the most reported dimension of burnout syndrome (BOS) among nurses (Arrogante & Aparicio-Zaldivar, 2017). Recent national research depicts an extremely alarming picture of the emotional health of Finnish nurses who work in acute care sectors. Among nurses working in hospitals, 28-34% of the registered nurses who were followed in 2023 belonged to the severe range of emotional exhaustion (MBI-EE 27 points) in the 2023 follow-up measurement of the large Finnish Public Sector Study cohort (which followed 9,586 nurses in 2018-2022), which consisted of 9,586 registered nurses (Kainalainen et al., 2024; Nagarajan et al., 2024). The situation is even worse when the data are analyzed by the types of units: in emergency departments, intensive care units and acute medical wards, severe emotional exhaustion reaches 41-52 percent (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL, 2024; Sääksjärvi et al. 2024; Andersson et al., 2022).

According to the repeated measurements of the national survey Well-being at Work in Health and Social Services, despite the slight decrease in the exhaustion level after the years of the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, they are still 10-15 percentage points higher than in 2018 (THL, 2024). Certainly, especially vulnerable populations can be distinguished. The rate of severe emotional exhaustion is nearly twice in nurses under the age of 35 years than their older counterparts and remains significant even after control variables such as unit type and working hours (Li et al., 2025). Equally, nurses with fixed-term or temporary contracts, which is common to newly graduated nurses, are at a 60-fold greater risk of experiencing severe exhaustion than permanent staff (Li et al., 2025; Kox et al., 2025). This phenomenon also varies regionally, as found in the university hospital districts in the south of Finland (in particular, HUS and TYKS), which have the highest rates, but smaller central hospitals in the east and north of Finland have relatively lower, but nevertheless alarming prevalence (THL, 2024).

2.1 RISK FACTORS OF EMOTIONAL EXHAUSTION AMONG FINNISH ACUTE CARE NURSES

Substantial number of studies has attributed workload, scheduling practices, leadership behaviour, and moral distress to the occurrence of emotional exhaustion in the Finnish healthcare system (Lusignani et al., 2017; Dall’Ora et al., 2022; THL, 2024; Sacadura-Leite et al., 2020). Opposite findings by international meta-analyses and large Finnish register-linked cohort studies all suggest the same group of core predictors and factors that are statistically significant as well as painfully familiar to anyone who has ever worked at least one shift in a Finnish university hospital or a central hospital emergency department (Koivula et al., 2000; Sacadura-Leite et al., 2020). In a survey of nurses working in two Finnish hospitals, moderate burnout was observed among nurses, but emotional exhaustion was high, and many nurses scored high related to workload and role ambiguity (Koivula et al., 2000).

The highest, most general force is the height of emotional and quantitative requirements coupled with low decision latitude which was described as the high-strain job 35 years ago in the demand-control-support model (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Practically, this translates to being in charge of critically ill patients and being under a continuous time constraint, placing patients onto the care schedule, and being aware that any failure to have a conversation with a patient or even a handoff may lead to severe outcomes yet having virtually no control over the number of staff members or the length of the shift, and more (Dall’Ora et al., 2022; THL, 2024).

The second significant causative factor is chronic understaffing and mandatory overtime. When secure ratios of nurses-to-patients are frequently violated (1:9-12 on the medical floors and 1:4-5 in emergency departments during evening shifts is not an exception), nurses have to work an unpaid oncall or even take a double shift in order to maintain the unit activity. Every additional hour of work outside the scheduled shift predisposes to high levels of emotional exhaustion the next month by about 8-12 prohibitions (Harma et al., 2022; THL, 2024).

The third one is frequent patient suffering, traumatic experiences, and death, with no sufficient debriefing or ritualized closure. According to Finnish ICU and emergency nurses, at an average, 2-4 patients die each month, dozens of severe traumas or aggressive episodes are witnessed each year, which leads to emotional burnout (so-called compassion fatigue) when emotional processing is not organized (Lusignani et al., 2017).

Absence of supervisor and co-worker support increases the impact of the aforementioned stressors tremendously. Even after adjusting for the workload, nurses who feel their ward manager is remote or unsupportive are at risk of severe exhaustion (Nagarajan et al., 2024). Another critical pathway is poor work-life balance and lack of physiological and psychological rest between shifts. According to Dall’Ora et al. (2022), over fifty percent of acute care nurses regularly report quick returns (less than 11 h between shifts) and prolonged series of night shifts, which cause cumulative sleep debt and insufficient cortisol recoveries (Dall’Ora et al., 2022).

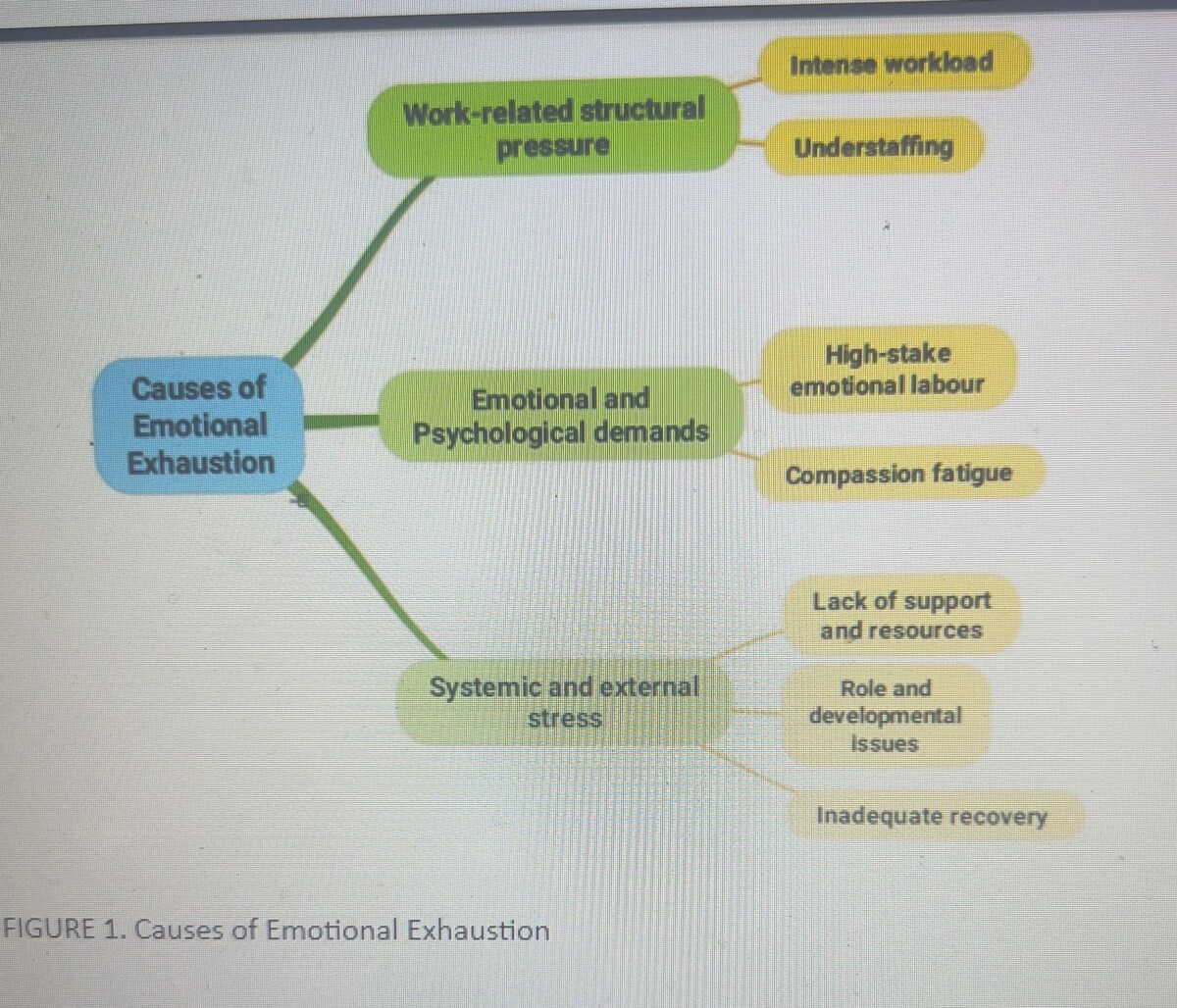

Furthermore, moral distress is also a significant factor for emotional exhaustion among the nurses. It involves the suffering of often knowing what the patient requires and being unable to deliver the required care due to the time constraint, the lack of necessary equipment, or the staff shortage which has become one of the most powerful predictors in recent Finnish studies (r = 0.58-0.65 in combination with emotional exhaustion) (Lusignani et al., 2017; THL, 2024). The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a spark: levels of exhaustion shot up to historic highs in 2020-2021 and, despite minor changes since the acute period, are 12-18 percentage points higher in 2024-2025 than in 2016-2019 (THL, 2024; Sääksjärvi et al. 2024). A lot of the structural issues that have been exposed or exacerbated by the pandemic, understaffing, cancelled holidays, undermined faith in leadership, etc, have not been improved. These factors are summarized in Figure 1 below.

3 CONSEQUENCES OF EMOTIONAL EXHAUSTION AMONG FINNISH NURSES

As established by numerous studies, emotional exhaustion serves as one of the strongest predictors of extended sickness leave, desire to abandon the profession, clinical depression, and in the worst case, substance use disorders (Panagioti et al., 2018; Chaves-Montero, A., Blanco-Miguel, P., & Ríos-Vizcaíno, 2025; Lusignani et al., 2017) are highly likely. High emotional exhaustion is a strong predictor of nurses taking extended sick leaves or leaving nursing altogether, leading to increased national shortage of registered nurses that is already estimated as 4,000-6,000 in specialized hospital care (Kestila & Karvonen, 2025).

The safety consequences on the patient are also frightening. Nurses that are emotionally drained demonstrate lower compliance with handhygiene measures and better medication errors, near-misses, and adverse events (Dall’Ora et al., 2022; Kangasniemi et al., 2022). These can lead to complications, prolonged hospitalization, and increased the risk of mortality in the high-acuity settings. The financial cost is enormous. Almost all nurse turnover and early retirement due to burnout and emotional exhaustion cost the public healthcare system of Finland over EUR300 million a year in terms of recruitment and agency staffing, training new staff and lost productivity (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2023). As the nursing workforce has become aging, and the problem of understaffing has remained constant since the 1990s, even when it comes to working in an acute care facility, emotional exhaustion has long gone unaddressed, jeopardizing the sustainability of the workforce and the quality of service provided to patients nationwide.

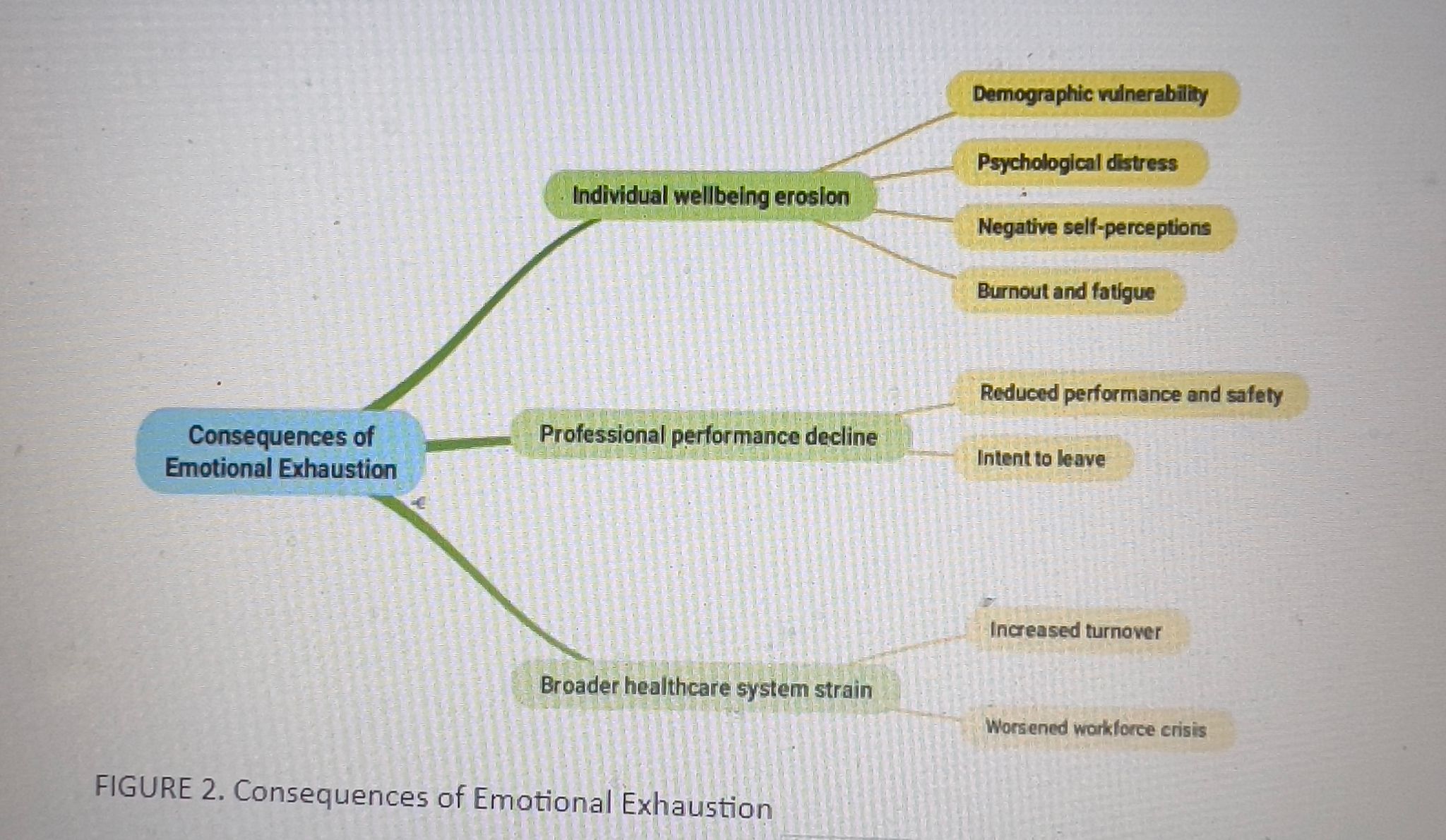

According to Flinkman et al. (2008), the young Finnish nurses are particularly vulnerable. The ground-breaking research study was able to determine that twenty six percent had greatly considered quitting which was directly related to personal burnout and emotional exhaustion because of unhealthy development chances and high stress load. (Flinkman et al., 2008). Gustafsson et al. (2022) found compassion fatigue as one of the effects of the emotional burnout occurrence in the acute care and the nurses noted the feeling of incompetence and emotional burnout because of the constant perception of suffering. These consequences are summarized in Figure 2 below. Research by Blasche et al. (2017) found out that high-level work-related fatigue was experienced by Finnish nurses who had worked 12-hour shifts, and emotional exhaustion was associated with inadequate recovery and distress, especially at a hospital. One out of every ten Finns is currently exposed to severe occupational burnout with a quarter of the population having been exposed (Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, 2024).

4 TARGETED INTERVENTIONS FOR EMOTIONAL EXHAUSTION IN FINNISH ACUTE CARE NURSES

Based on current world-wide and Finnish-based studies, empirical evidence was able to point out intervention strategies which this nurse experience can be reduced or controlled. These are not universal strategies but rather acute care grind strategies. This intervention may be divided into two:

4.1 INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL INTERVENTIONS

It has been demonstrated that person-directed strategies give people the ability to reclaim their energy, that is why they experience less emotional exhaustion due to their promotion of mindfulness and coping skills (Lee & Cha, 2023; Brook et al., 2021). These strategies include:

4.1.1 Mindfulness and Stress Management Training:

This intervention aims at reducing the level of stress and enhancing the quality of life of the patient by using mindfulness meditation. Interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) or psychological skills training have reduced exhaustion ratings by instructing nurses on how to go through emotional labor without exhaustion (Goodwin et al., 2024; Brook et al., 2021). A meta-analysis by Wang et al. (2024) on the effectiveness of these interventions, affirmed that it can increase resilience and reduce burnout by 20-30% in high-stress environments. Through the incorporation of apps or group sessions, Finnish acute care nurses would compensate the “bruises in the soul” caused by compassion fatigue (Zhang et al. 2025; Gustafsson & Hemberg, 2022; Wylde et al., 2017).

4.1.2 Self-Care Routines and Coping Strategies

Self-care is not full, but fuel; yoga sessions, journaling, etc. Emotion-centered strategies such as relaxation techniques, physical activity, and social support groups have been shown to refresh nurses, and one Finland-oriented review of the studies has shown positive effects in alleviating insomnia and fatigue (Jaber et al., 2025). Problem-oriented interventions (cognitive reframing a problem as a learning opportunity, etc.) are also bright, particularly among young nurses at risk of quitting (Jaber et al., 2025). It is recommended that emergency medics apply personalized music therapies, which may be a low-cost win to the high-tech nurse population in Finland.

4.1.3 Therapy and Emotional Support

A request to be assisted does not make one weaker, it only reinforces a person. Psychoeducational programs are also known as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which has been effective in addressing the issue of emotional exhaustion. In particular, Sharin et al., (2024) hypothesized that exhaustion symptoms are reduced by half on psychoeducational programs that deal with moral distress. Mental health service and peer support networks, recommended by WHO are game changers in Finland, where one out of ten experience severe burnout as a way of nurses dealing with pandemic echoes and everyday traumas.

4.2 Organizational and Team-Level Interventions

Fixing the system from within nurses thrive when the environment supports them, hence the need for organizational intervention. Organizational intervention strategies tackle root causes like staffing shortages and role ambiguity, which hit Finnish acute care hard (Petersen et al., 2023). Blending these with individual efforts yields the best results (Zhang et al., 2025). Such organizational interventions include:

4.2.1 Workload Management and Staffing Boosts.

This includes overhaul to end the interminable marathon in shifts ḅy putting quantitative requirements at a floor (as by capping the number of patients) or creating flexible schedules serves to reduce exhaustion without regard to setting (Petersen et al., 2023). Hiring of additional staff or AI in the administration of the country would leave nurses to attend to the patients in Finland, which is poised to have a shortage of staff, and this model has already worked in nursing homes (Elshikh, 2024). Such policies as mandatory breaks and vacation, which ANA promoted, provide recovery, and based on the research, these policies are associated with 15-25% reduced burnout rates (American Nurses Association, n.d.).

4.2.2 LEADERSHIP AND TEAM BUILDING

Leadership and Team Building: Equipping nurses with leadership skills and training will fortify them to withstand the day-to-day occupational stress. Apart from the strength to remain persevering, studies have found that leadership skills and training can enhance work engagement and cut exhaustion by improving teamwork and cooperation, which is essential for Finnish nursing homes and hospitals. Additionally, interventions such as workshops on resilience development and interprofessional collaboration have the potential to instill the ability to meet the emotional demands in acute care. (Kohnen et al., 2024; Fassai et al., 2022)

4.2.3 Psychological and Resource Support

Embed mental health into the workplace. On-site counseling debriefs after tough shifts, and access to treatment for insomnia (prevalent in shift workers) are vital, per WHO insights from Finland. Structural changes, like better resource allocation, addressing moral injury from shortages, boosting satisfaction and retention. (Richter et al., 2016; Järnefelt et al., 2020; Grünberger et al., 2025).

Author: Jamiu Alabi Opeyemi

References:

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Nurse burnout: What is it & how to prevent it. https://www.nursingworld.org/content-hub/resources/workplace/what-is-nurse-burnout-how-to-prevent-it/

Andersson, M., Nordin, A., & Engström, Å. (2022). Critical care nurses’ perception of moral distress in intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic–A pilot study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 72, 103279.

Blasche, G., Bauböck, V. M., & Haluza, D. (2017). Work-related self-assessed fatigue and recovery among nurses. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 90(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-016-1187-6

Brook, J., Aitken, L. M., MacLaren, J.-A., & Salmon, D. (2021). An intervention to decrease burnout and increase retention of early career nurses: A mixed methods study of acceptability and feasibility. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00524-9

Chaves-Montero, A., Blanco-Miguel, P., & Ríos-Vizcaíno, B. (2025). Analysis of the Predictors and Consequential Factors of Emotional Exhaustion Among Social Workers: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(5), 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050552

Dall’Ora, C., Saville, C., Rubbo, B., Turner, L., Jones, J., & Griffiths, P. (2022). Nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. International journal of nursing studies, 134, 104311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104311

Elshikh, M. (2024). Mitigating burnout: Identifying risk factors and effective strategies for nurses [bachelor’s thesis]. Theseus. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/875476/Elshikh_Marwa.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. (2024, October 2). Severe occupational burnout has increased. https://www.ttl.fi/en/topical/press-release/severe-occupational-burnout-has-increased

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). (2024). Well-being at work in health and social services 2024. THL Statistical Report 18/2024. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/150807/SR_2_2025_en_.pdf?sequence=11&isAllowed=y

Flinkman, M., Laine, M., Leino-Kilpi, H., Hasselhorn, H. M., & Salanterä, S. (2008). Explaining young, registered Finnish nurses’ intention to leave the profession: a questionnaire survey. International journal of nursing studies, 45(5), 727–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.12.006

Galanis, P., Moisoglou, I., Katsiroumpa, A., Gallos, P., Kalogeropoulou, M., Meimeti, E., & Vraka, I. (2025). Workload increases nurses’ quiet quitting, turnover intention, and job burnout: evidence from Greece. AIMS public health, 12(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2025004

Goodwin, C., McCormack, M., Andrews, J., Costanzo, G., Lekwa, F., & Smith, P. R. (2024, September 20). Interventions to overcome nurse burnout. Oklahoma Nursing Association. https://www.myamericannurse.com/interventions-to-overcome-nurse-burnout/

Grünberger, T., Höhn, C., Schabus, M., & Laireiter, A.-R. (2025). Sleep-related factors in shift workers: A cross-sectional cohort pilot study to inform online group therapy for insomnia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111681

Gustafsson, T., & Hemberg, J. (2022). Compassion fatigue as bruises in the soul: A qualitative study on nurses. Nursing ethics, 29(1), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330211003215

Jaber, M. J., Bindahmsh, A. A., Baker, O. G., Alaqlan, A., Almotairi, S. M., Elmohandis, Z. E., Qasem, M. N., AlTmaizy, H. M., du Preez, S. E., Alrafidi, R. A., Alshodukhi, A. M., Al Nami, F. N., & Abuzir, B. M. (2025). Burnout combating strategies, triggers, implications, and self-coping mechanisms among nurses working in Saudi Arabia: a multicenter, mixed methods study. BMC nursing, 24(1), 590. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03191-w

Järnefelt, H., Härmä, M., Sallinen, M., Virkkala, J., Paajanen, T., Martimo, K.-P., & Hublin, C. (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy interventions for insomnia among shift workers: RCT in an occupational health setting. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 93(5), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01504-6

Kainalainen, A., Korhonen, P., Penttinen, M. A., & Liira, J. (2024). Job stress and burnout among Finnish municipal employees without depression or anxiety. Occupational medicine (Oxford, England), 74(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqae019

Kestilä, L., & Karvonen, S. (Eds.). (2025). Solutions for building a sustainable society: Population health and wellbeing report 2025 (Report 8/2025). Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/151481/URN_ISBN_978-952-408-517-5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Kohnen, D., De Witte, H., Schaufeli, W. B., Dello, S., Bruyneel, L., & Sermeus, W. (2024). Engaging leadership and nurse well-being: the role of the work environment and work motivation-a cross-sectional study. Human resources for health, 22(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00886-6

Koivula, M., Paunonen, M. and Laippala P. (2000) Burnout among nursing staff in two Finnish hospitals. Journal of Nursing Management, 8, 149-158. Doi:10.1046/j.1365-2834.2000. 00167.x

Kox, J. H. A. M., Groenewoud, J. H., Bakker, E. J. M., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A., Runhaar, J., Miedema, H. S., & Roelofs, P. D. D. M. (2020). Reasons why Dutch novice nurses leave nursing: A qualitative approach. Nurse education in practice, 47, 102848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102848

Lee, M., & Cha, C. (2023). Interventions to reduce burnout among clinical nurses: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports, 13(1), 10971. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38169-8

Li, L., Huang, C. H., Lee, Y. C., & Wu, H. H. (2025). Emotional exhaustion among operating room and general ward nurses: evidence from a regional hospital in Taiwan. Frontiers in public health, 13, 1648696. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1648696

Lusignani, M., Giannì, M. L., Re, L. G., & Buffon, M. L. (2017). Moral distress among nurses in medical, surgical and intensive-care units. Journal of nursing management, 25(6), 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12431

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (2023). Costs of early retirement and turnover in health care. Report 2023:15. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/12/finland-country-health-profile-2023_98a8f1c1/e7af1b4d-en.pdf

Nagarajan, R., Ramachandran, P., Dilipkumar, R., & Kaur, P. (2024). Global estimate of burnout among the public health workforce: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human resources for health, 22(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-024-00917-w

Panagioti, M., Geraghty, K., Johnson, J., Zhou, A., Panagopoulou, E., Chew-Graham, C., Peters, D., Hodkinson, A., Riley, R., & Esmail, A. (2018). Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(10), 1317–1330. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713

Petersen, J., Wendsche, J., & Melzer, M. (2023). Nurses’ emotional exhaustion: Prevalence, psychosocial risk factors and association to sick leave depending on care setting-A quantitative secondary analysis. Journal of advanced nursing, 79(1), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15471

Puolakanaho, A., Tolvanen, A., Kinnunen, S. M., & Lappalainen, R. (2020). A psychological flexibility-based intervention for burnout: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.007

Richter, K., Acker, J., Adam, S., & Niklewski, G. (2016). Prevention of fatigue and insomnia in shift workers-a review of non-pharmacological measures. The EPMA journal, 7(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13167-016-0064-4

Sääksjärvi, K., Elonheimo, H. M., Ikonen, J., Lehtoranta, L., Parikka, S., Härkänen, T., Vihervaara, T., Sainio, P., Jääskeläinen, T., Suominen, A. L., Harjunmaa, U., Mäkelä, P., Lahti, J., Kaartinen, N. E., Koskinen, S., & Lundqvist, A. (2024). Cohort Profile: Healthy Finland Survey. International journal of epidemiology, 54(1), dyae166. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyae166

Sharin, A. I., Jinah, N., Bakit, P., Adnan, I. K., Zakaria, N. H., Mohmad, S., Ahmad Subki, S. Z., Zakaria, N., & Lee, K. Y. (2024). Psychoeducational Burnout Intervention for Nurses: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR research protocols, 13, e58692. https://doi.org/10.2196/58692

Tuomaala, N., & Barrow, A. (2025). Challenges encountered by foreign-born nurses in the Finnish Healthcare workforce: A critical reflective approach. Oamk Journal, 41(2025). https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/881939

Wang, L., Li, G., Liu, J., Diao, Y., & Zhuo, Y. (2024). Summary of best evidence for interventions for nurse burnout. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.27.24309626

Wylde, C. M., Mahrer, N. E., Meyer, R. M. L., & Gold, J. I. (2017). Mindfulness for novice pediatric nurses: Smartphone application versus traditional intervention. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 36, 205-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.06.008

Zhang, H., Xia, Z., Yu, S., Shi, H., Meng, Y., & Dator, W. L. (2025). Interventions for Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nursing & health sciences, 27(1), e70042. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.70042